What is LHON?

Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON) is a rare, inherited form of mitochondrial disease resulting in rapid central vision loss.Footnote1,Footnote2 The management of LHON remains challenging, and the visual prognosis is quite poor.Footnote1 German ophthalmologist Theodore Leber defined it as a clinical condition in 1871.Footnote2

LHON was the first human condition linked to point mutations in the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). These mutations affect subunit genes of complex I.Footnote3 LHON presents with subacute, simultaneous or sequential, bilateral painless loss of central vision due to selective degeneration of the retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) and their axons.Footnote2 These cells are particularly vulnerable to mitochondrial dysfunction leading to optic nerve atrophy and loss of central vision.Footnote2 Most patients with LHON end up legally blind.Footnote1

-

LHON is a mitochondrial disorder that results from point mutations in the mitochondrial DNA that encode components of respiratory complex 1 (See figure below).Footnote4 Approximately 90% of the LHON cases come from three primary mtDNA mutations (m.3460G>A in MT-ND1, m.11778G>A in MT-ND4, and m.14484T>C in MT-ND6) that are maternally inherited.Footnote5

Although a pathogenic mutation is the key factor, an environmental trigger is also required.Footnote6 Around one in three cases also appears to be sporadic with no definitive family history.Footnote7 Other rare mtDNA mutations account for a further ~10% of the LHON cases.Footnote8 In addition, a second form of LHON mutation in a nuclear encoded gene, DNAJC30, has also been established—described as an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance for LHON (arLHON).Footnote8

Membrane complexes in the mitochondrial respiratory chainsFootnote4

Adapted from Carelli V, et al. 2019.4

ADP, adenosine diphosphate; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; CyC, cytochrome C; LHON, Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy; NAD+/NADH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide -

LHON is a common cause of inherited visual failure, affecting at least 1 in 30,000 individuals in the UK.Footnote9 LHON affects predominantly men in their 20s or 30s and is most commonly seen in teenage boys and young men, which account for 80% of the new cases.Footnote1,Footnote7

However, it can occur in individuals of all ages, including children and the elderly, with the age of onset being higher in women.Footnote7 Men are four to five times more likely to be affected than women, but neither gender nor mutational status significantly influences the timing and severity of the initial visual loss.Footnote5 Recent evidence also suggests a protective role of estrogen and could explain LHON vision loss in menopausal women, given the declining levels of oestrogen.Footnote10

Who’s at risk

Genetic confirmation of an LHON mutation means everyone on the maternal bloodline is at riskFootnote11

LHON affects both men and womenFootnote5

LHON is most frequently diagnosed in teenagers and young menFootnote7

What LHON eyesight looks like

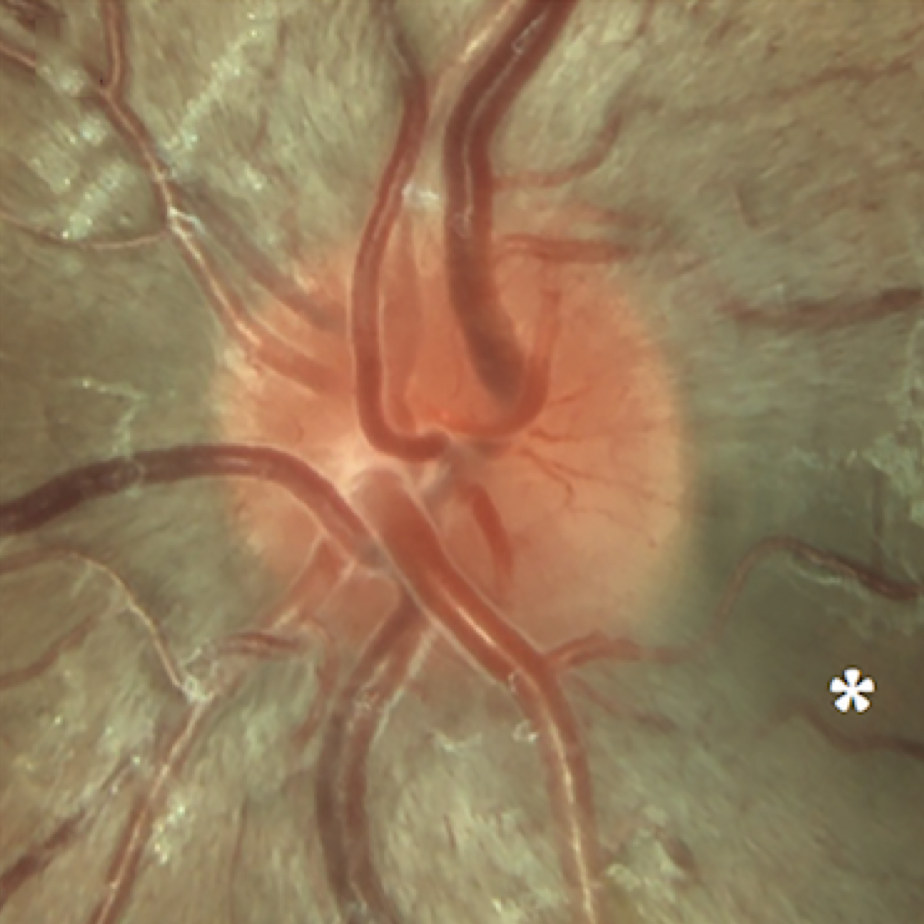

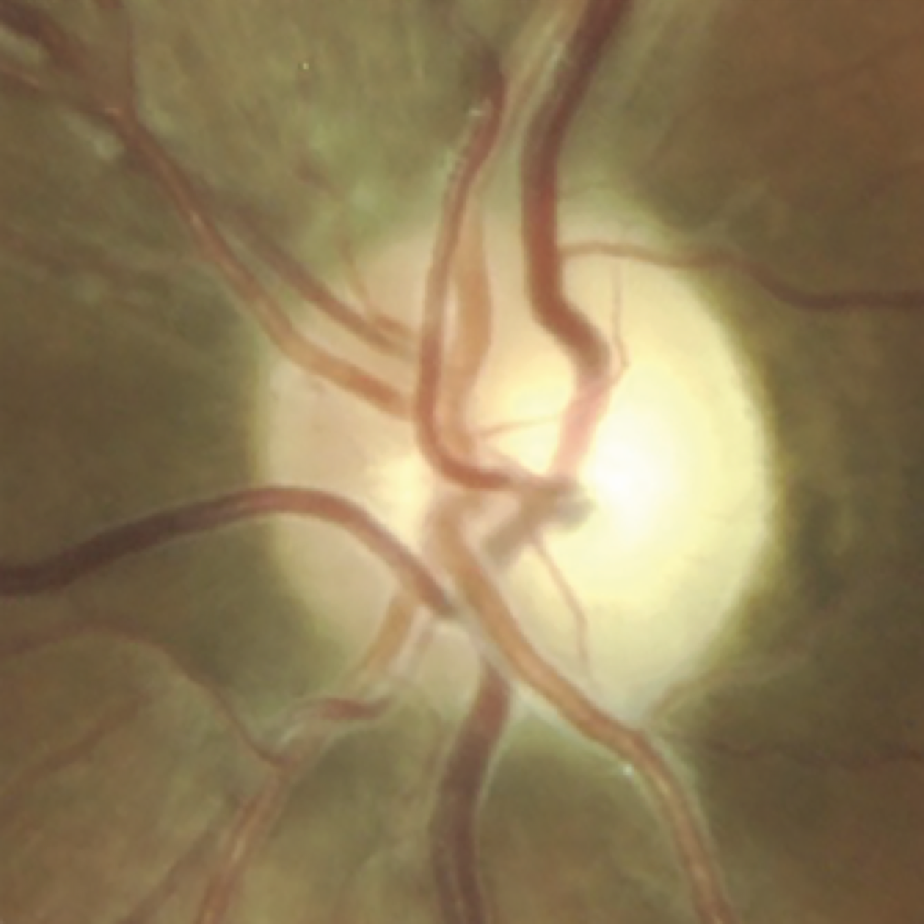

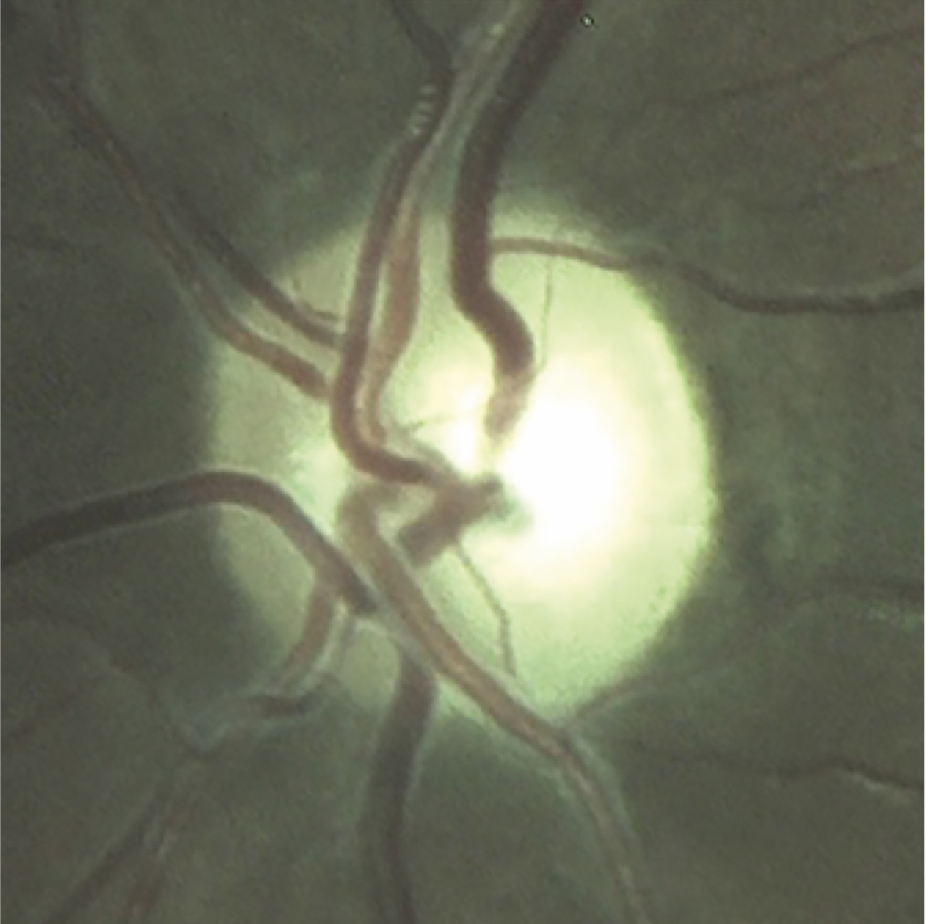

People with LHON experience sudden, painless visual loss either in both eyes simultaneously (one in four cases) or sequentially with the second eye showing symptoms within 8 weeks (three in four cases).Footnote7The most characteristic feature of LHON is an enlarging central or centrocecal scotoma.Footnote7 As the field defect increases in size and density, visual acuity deteriorates to the level of counting fingers or worse.Footnote5,Footnote7

Signs and symptoms

Patients are usually entirely asymptomatic until they develop painless visual blurring affecting the central visual field in one eye (acute phase).Footnote5 Similar symptoms appear in the other eye within weeks or months, with at least 97% of affected individuals having bilateral involvement within one year.Footnote5 Unilateral LHON is very rare.Footnote7

LHON red flags

- Bilateral, painless subacute visual failure that develops during young adult lifeFootnote5

- No periocular pain, no pain at eye mobilisationFootnote4,Footnote5

- Disc hyperaemia, oedema of the peripapillary retinal nerve fibre layer, retinal telangiectasia, and increased vascular tortuosityFootnote5

- ~20% of affected individuals show no fundal abnormalities in the acute stage

- Optic disc atrophyFootnote5

- Green-red dyschromatopsiaFootnote5,Footnote11

- Optic nerve dysfunction and absence of other retinal disease alterations on electrophysiologic studiesFootnote5

- Pupillary reflexes are preserved in the early phase (6–12 months) and patients usually report no pain on eye movementFootnote4,Footnote11

Potential risk factors and triggers

A number of environmental factors are also known to trigger LHON in unaffected carriers.Footnote13 Discussions with patients should involve avoiding potentially preventable lifestyle risk factors for vision loss:Footnote13,Footnote14

Risk factors

Further triggers of LHON may include:

*This class of medication could be associated with interfering with mitochondrial respiratory function.13

-

Theodorou-Kanakari A, et al. Adv Ther. 2018;35:1510–18.

Kirches E, et al. Current Genomics. 2011;12:44–54.

Carelli V, et al. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26:139–50.

Carelli V, et al. Eur Ophthalmic Rev. 2019;13 Suppl 2.

Yu-Wai-Man P and Chinnery PF. Leber Hereditary Optic Neuropathy. GeneReviews® [Internet]. 2021. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1174/. Accessed: March 2023.

Ghelli A, et al. J Biol Chem. 2003:278:4145–50.

Karaarslan C. Adv Ther. 2019:36;3299–307.

Stenton SL, et al. J Clin Invest. 2021:15;131:e138267.

Kirkman MA, et al. IOVS. 2009;50:3112–15.

Asanad S, et al. J Curr Ophthalmol. 2019:251–53.

Atlas of Leber’s Hereditary Optic Neuropathy, 2018, MEDonline, ISBN: 978-90-828166-0-0

Meyersen C, et al. Clin Ophthal. 2015;9:1165–76.

Sadun A, et al. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2011:109–17.

Yu-Wai-Man P, et al. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2011;30:81–114.

Disclaimer: The information on this website is intended only to provide knowledge of Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON). This website has been produced by Chiesi Pharmaceuticals. The website has been developed in accordance with industry and legal standards to provide information for healthcare professionals about LHON. Chiesi Pharmaceuticals makes every reasonable effort to include accurate and current information. However, the information provided in this website is not exhaustive.

United Kingdom

United Kingdom  Global

Global  Sweden

Sweden  Greece

Greece  Norway

Norway